How to Load Sandwell & Smith Gravity Data in Python?

Introduction

Mapping the depth of the oceans globally was one of the greatest successes of geophysics in the 20th century. Without bathymetry, we would not know the locations of mid-ocean ridges, volcanic seamounts, and transform faults, to name a few, all of which are key elements of plate tectonics.

But mapping the seafloor is hard, tedious and costly - shipborne measurements, while accurate, cover only tiny portions of the ocean surface. And the distribution of those measurements (made first by manual sounding, later with sonars) is very uneven: large parts of the oceans, especially in the southern hemisphere remain completely unexplored. In fact, only 8% of the oceanic surface is mapped accurately (Smith et al., 2017).

The best solution available to us to fill the gaps is satellite altimetry (Smith and Sandwell, 1997). The bathymetry is derived from gravity anomalies that are calculated from measurements of the sea surface height. The basic principle behind this technique is that the underwater topography (ridges and troughs) induce small changes in the gravity pull around them, deforming the sea surface.

The height of the sea surface can be measured very accurately by specialised satellites, which have seen their number and quality increase significantly in the last 10 years. The latest versions of global gravity anomaly maps (Sandwell and Smith version 24.1, DTU version 15, Getech’s Multi-Sat) show remarkable improvements over the previous ones (Sandwell et al., 2014; Andersen and Knudsen, 2016).

In this post, I explain how to obtain global gravity data and how to display them in a map with Python.

Get the data

The global marine gravity data from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego is commonly known as the “Sandwell and Smith” gravity dataset, even though several other authors have contributed to its development since the 1990’s. The latest version, v24.1, can be downloaded on this FTP site. The file that we need is grav.img.24.1.

This large file (712 MB) actually contains a map of the gravity anomalies, projected with a spherical Mercator projection.

Convert the data using GMT

To obtain the grid of gravity anomalies in a geographic coordinate system, the img file needs to be “unprojected” and converted to a different format. This can be done with a special tool available in GMT (Generic Mapping Tools). The following command will convert the img file to a new file called grav_v24.nc. The -R option is normally used to extract portion of the grid, but here the values cover the entire extent of the grid. The -S returns the data in mGal by multiplying the data by 0.1. Finally, the -V option provides a verbose output, so that we can see what is going on.

img2grd grav.img.24.1 -Ggrav_v24.nc -R0/360/-80.738/80.738 -S0.1 -VThe output of this command shows the following (I used version 5.4.2):

img2grd: Expects grav.img.24.1 to be 21600 by 17280 pixels spanning 0/360.0/-80.738009/80.738009.

img2grd: To fit [averaged] input, your grav.img.24.1 is adjusted to -R0/360/-80.738008628/80.738008628.

img2grd: The output grid size will be 21600 by 17280 pixels.

img2grd: Created 21600 by 17280 Mercatorized grid file. Min, Max values are -366.39999 943.79999

img2grd: Undo the implicit spherical Mercator -Jm1i projection.

grdproject: Processing input grid

grdproject: Transform (0/360/-80.738/80.738) <-- (0/360/0/287.999892786) [inch]

grdproject: gmt_grd_project: Output grid extrema [-957.6/967.8] exceed extrema of input grid [-366.4/943.8] due to resampling

grdproject: gmt_grd_project: See option -n+c to clip resampled output range to given input range

grdproject: Proj4 string to be converted to WKT:

+proj=longlat +no_defsNote that the img2grd command can only output the result in the default format of GMT, which is netCDF.

Convert to Geotiff

The next step would typically be to load the grid, for example in a Numpy array if you work in Python. A powerful library for reading raster data in Python is rasterio. Unfortunately, the underlying library of rasterio, GDAL, that provides the drivers to read raster data, fails to load the netCDF that we have just created. So an additional step is necessary in order to convert this file to a Geotiff. I have used this GMT command successfully:

grdconvert grav_v24.nc -Ggrav_v24.tif=gd:GTiFF -VResample to a square cell size

The conversion to a geographic coordinate system in the first step has created a grid with a rectangular cell size. Here is an excerpt of the output of grdinfo grav_v24.nc:

grav_v24.nc: x_min: 0 x_max: 360 x_inc: 0.0166666666667 name: longitude [degrees_east] n_columns: 21600

grav_v24.nc: y_min: -80.738 y_max: 80.738 y_inc: 0.00934467592593 name: latitude [degrees_north] n_rows: 17280We can see that the increment along the x axis (x_inc) is smaller than the increment along the y axis (y_inc).

While this file is still valid for analysis as it contains more information, I do need a square cell size for displaying the map in the next step. And I don’t need the full resolution, so let’s resample the grid to a 5 arc-minute resolution with GDAL:

gdalwarp -tr 0.0833333333333 0.0833333333333 -r bilinear "grav_v24.tif" "grav_v24_5min.tif"Reading the data in Python

A simple way to access the data in our new grid is to load it in a Numpy array. There are various ways to do this. Here is an example:

import scipy

data = scipy.ndimage.imread('grav_v24_5min.tif')The result is an array of shape (1938, 4320). One issue with this approach is that the geographic information about the grid is lost: things like the cell size and the location of the origin are crucial for displaying and processing the data properly.

Display the data with interpies

Using rasterio as a base for reading raster data, I have developed a Python module called [interpies](https://github.com/jobar8/interpies). This can be used to analyse, process and display gridded geophysical data such as gravity anomalies. The installation of interpies requires several dependencies that are detailed in the GitHub repository.

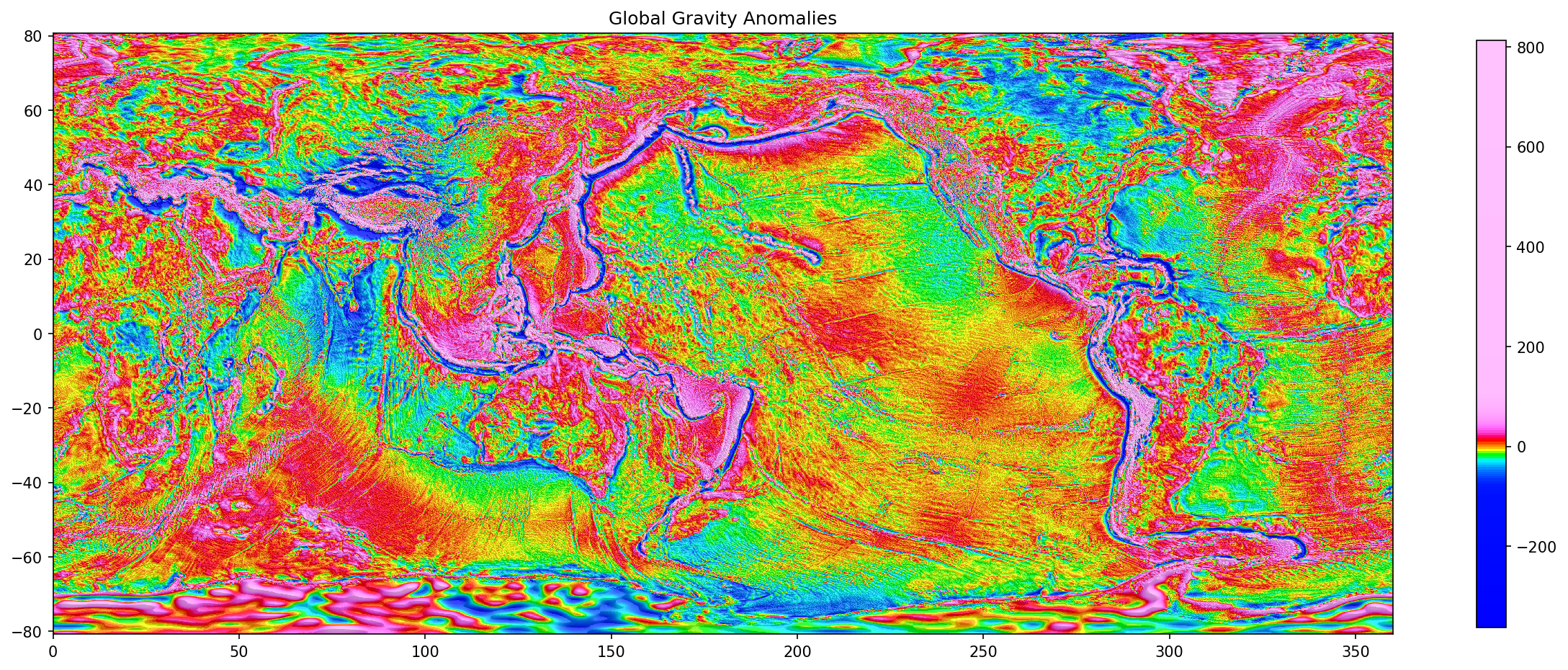

The main idea of interpies is that gridded data can be loaded into a grid object, which is then processed using methods that can be chained together to obtain relatively complex outputs with the minimum amount of code. Just reading and displaying the grid is done in this way:

import interpies

grid1 = interpies.open('grav_v24_5min.tif')

ax = grid1.show(figsize=(20,12), title='Global Gravity Anomalies')Information about the grid can be displayed with the info method:

> grid1.info()

* Info *

Grid name: grav_v24_5min

Filename: grav_v24_5min.tif

Coordinate reference system: epsg:4326

Grid size: 4320 columns x 1938 rows

Cell size: 0.08333

Lower left corner (pixel centre): (0.042,-80.720)

Grid extent (outer limits): west: 0.000, east: 360.000, south: -80.762, north: 80.738

No Data Value: nan

Number of null cells: 0 (0.00%)

* Statistics *

mean = -0.2992794825345438

sigma = 33.31866132985248

min = -362.504638671875

max = 814.0865478515625There are lots of other methods available in interpies and they will be detailed in future posts.

References

Andersen, O. B., & Knudsen, P. (2016). Deriving the DTU15 Global high resolution marine gravity field from satellite altimetry. Abstract from ESA Living Planet Symposium 2016, Prague, Czech Republic.

Sandwell, D. T., R. D. Müller, W. H. F. Smith, E. Garcia, R. Francis (2014), New global marine gravity model from CryoSat-2 and Jason-1 reveals buried tectonic structure, Science, Vol. 346, no. 6205, pp. 65-67, doi: 10.1126/science.1258213.

Smith, W. H. F., K. M. Marks, and T. Schmitt (2017), Airline flight paths over the unmapped ocean, Eos, 98, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO069127.

Smith, W. H. F., and D. T. Sandwell (1997), Global seafloor topography from satellite altimetry and ship depth soundings, Science 277(5334), 1956–1962, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5334.1956.